Shift

Today’s youth begin hitting by batting off a tee. It’s safe, allows every child to put the ball in play, and importantly, teaches the kids to level their swings. You will also see some of the best MLB hitters in the game hitting from a tee in their pre-game work (Anthony Rizzo is a good example). For the best hitters in the game, it’s a way to get back to the fundamentals of batting. In hitting off a tee, MLB batters can focus on driving the ball up the middle or the other way. Indeed, hitting the ball to the opposite field has become a lost art. To address the frequency of managers employing shifts, MLB adopted a rule this season that prohibits their use.

What is a shift? It’s a defensive realignment from the usual positions of fielders to crowd one side of the infield. Managers use shifts so that fielders are in a better position to handle hard ground balls hit by pull hitters. Many baseball historians point to the 1940s as the genesis of shifts when Cleveland Indians manager, Lou Boudreau, employed a defensive shift to thwart Red Sox star Ted Williams. Yet, others trace shifts to another great hitter named Williams, Ty Williams, who played for the Cubs and the Phillies from 1912 to 1930.

Ty Williams was one of the more feared lefthanded hitters of his era. In fact, in the prime of Bath Ruth’s career, 1923-1928, Williams was only second to Ruth in home runs. Williams led the National League in home runs in four seasons and totaled 251 in his career. He was described as a dead pull hitter, so much so that opposing managers would move the entire defense to the right side of the field.

The other ”Williams Shift”, or perhaps better known as the “Boudreau Shift”, was a brainchild of Cleveland Indians’ manager, Lou Boudreau, between games of a July 14, 1946, doubleheader when the Indians faced Ted Williams’ Red Sox. Boudreau himself played for 15 seasons in the American League and won the 1944 AL batting title. As player manager, Boudreau would often try to get in the heads of star players in the league. By using a shift against Ted Williams, he thought he could coax the great hitter into minimizing his power. In his book, Player-Manager, Boudreau remarked: “I have always regarded the Boudreau Shift as a psychological, rather than a tactical, victory”.

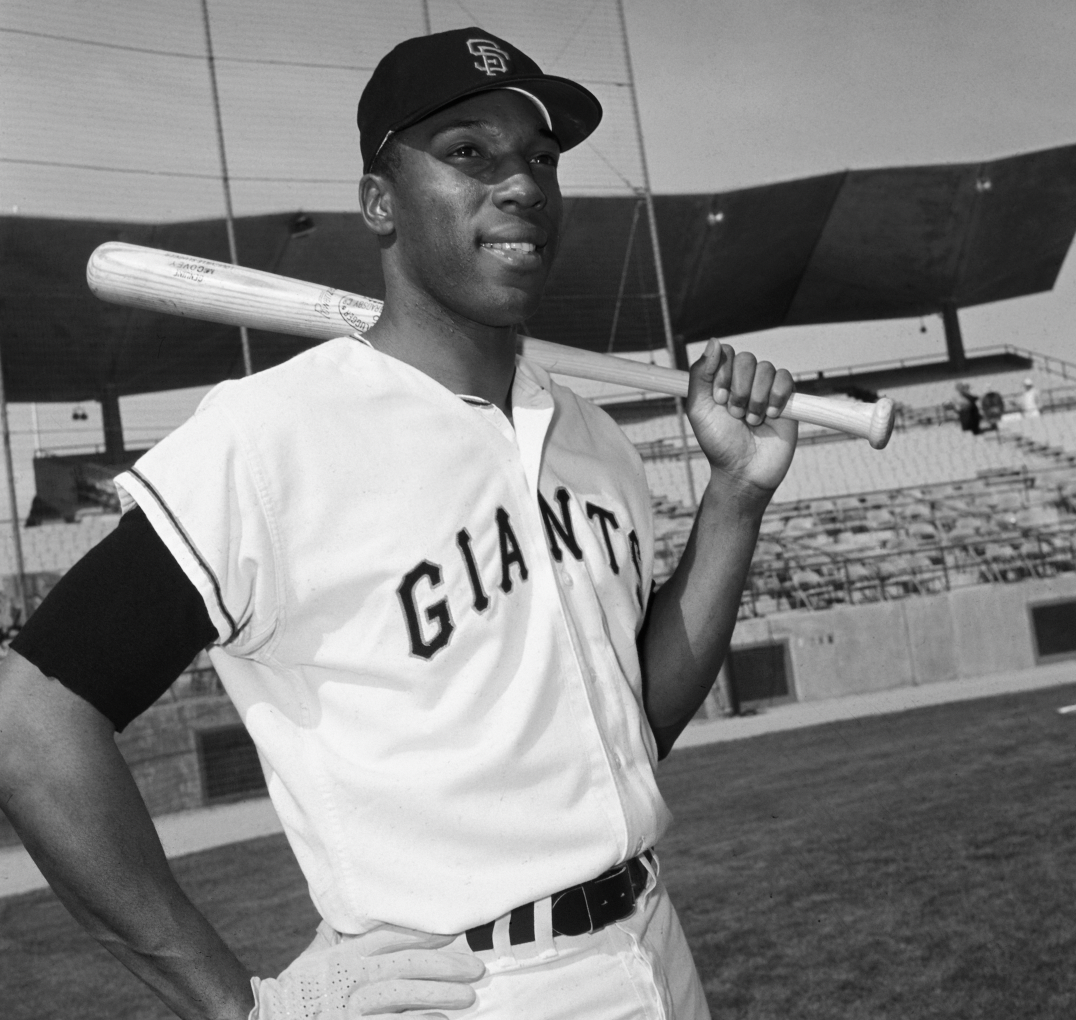

The most feared MLB left handed hitter in my boyhood was Willie McCovey, the Giants’ Hall of Fame first baseman. In his 22-year career, McCovey was a three-time NL home run leader, six-time All-Star, and 1969 NL Most Valuable Player. Known as “Stretch”, he was a line drive pull hitter. Pitching great Bob Gibson of the Cardinals deemed him “the scariest hitter in baseball”. Managers, such as the Reds’ Sparky Anderson, consistently employed a shift against McCovey. Anderson said this about McCovey: “If you pitch to him, he’ll ruin baseball. He’d hit 80 home runs. There’s no comparison between McCovey and anybody else in the league.”

While managers often used shifts since then, it wasn’t until the last decade when they become extremely popular. In 2016 the highest team shift rate rose to 34% of their opponent’s at bats and in 2022 it skyrocketed to 52.5% of the time. MLB began to address the increased use of shifts on the minor league level. As part of an agreement with MLB, the independent Atlantic League of Professional Baseball in 2019 restricted the shift and required two infielders to be positioned on either side of second base. In 2022, shift restrictions were used at the AA and A levels (four players required to be in the infield with two on each side of second).

Per the terms of a new collective bargaining agreement after the 2021 lockout, MLB was given the permission to restrict infield shifts beginning in 2023. And it did just that! A new rule was added that requires two infielders to be positioned on either side of second before a pitch is thrown. If the defensive team violates the rule, the team at the plate can choose to have the pitch awarded as a “ball” or take the outcome of the play. We have not as yet seen a violation of the switch restriction during the season.

Baseball traditionalists are for the most apart aghast at the restriction. You often hear the grumblings of don’t help the hitters who can’t adjust their swings to go the other way. My favorite take on the mindset of a batter facing a shift prior to the rule change is that of former manager Joe Maddon: “You have three choices: You can try and hit it and beat the shift. That’s going to give you a single, but now you’re doing something against what you’re best at, so the defense wins. You can hit into the shift, and the defense wins. Or you can try not to let the infielders catch the batted ball. No ground balls and no popups. Try to stand on second base. That’s Option C.”

I’ll take Option C any day of the week.

Until next Monday,

your Baseball Bench Coach